CUTTING THE CARBON CRAP IN REAL ESTATE VALUATIONS; PRICING THE DECARBONISATION TRANSITION

December 21, 2021

Article source: December 2021 issue of European Valuer the publication of the European Group of Valuer’s Associations (TEGOVA)

By Xavier Jongen, Managing Director, Catella Residential Investment Management

“Code Red for Humanity”

The ominous warning contained in the latest UN IPCC climate report that global warming is showing signs of spiralling out of control, should be lighting a fire under real estate investors and valuers to bring us to the realisation that we need to engage the full power of market forces in bringing about the decarbonisation of our industry as rapidly as possible. But is the energy transition to a net carbon neutral, or even an operation-ally negative carbon built environment occur-ring with the urgency and speed it needs to?

I would argue that we’ve barely started, because we’re not pricing the costs of decarbonisation into investment transactions, we’re mostly merely labelling their energy efficiency. Without a market mechanism for capturing the ‘greenium,’ or the true ‘Value’ incentive of investing in decarbonisation, BREEAM, LEED, or any other certification could become only token markers alongside the road to the climate change cliff edge.

We in the real estate industry, including the valuation profession, lie at the epicentre of the climate problem and must therefore be able to play a large part in mitigating, and adapting to, its consequences. We should all know the numbers by now. The built environment contributes around 35% of global carbon emissions, of which around 75% comes from operations, mainly heating and cooling, and 25% from the construction process. My market, residential, including rental and owner occupier, is the largest contributor among property sectors. Unsurprisingly, as that’s where the eight billion of us on the planet live.

Institutional Investors are Changing the Rules of Engagement through Double Materiality

The world is going to have to move rapidly towards pricing into investments ‘Value’ that wasn’t previously considered in financial terms, if we are to stand any chance of seriously tackling climate change, or, for that matter, the other great challenge of our age, social inequality. The price point, as a signal of value, is absolutely central to the notion of capitalism. Fortunately, there are signs that this could be starting to occur at the regulatory level. The European Commission has asked the EU pensions supervisor EIOPA to assess the potential need to introduce the notion of ‘double materiality’ in Europe’s pension financing framework. Double materiality would require pension funds to equally weigh climate impact and societal factors alongside financial risks and returns in their investment decisions. The double materiality concept is already present as a qualifier for the Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation’s Article 9 ‘dark green’ investment fund categorisation.

A paradigm shift in the weighing of pension liabilities, risks and returns from a mainly financial focus under double materiality would, for example, also be expected to fundamentally change the basis on which capital is allocated in the Dutch institutional investment sector — the largest private pensions market in the EU, the fourth biggest pool of ‘moral money’ in the world, and also a major group of investors in real estate.

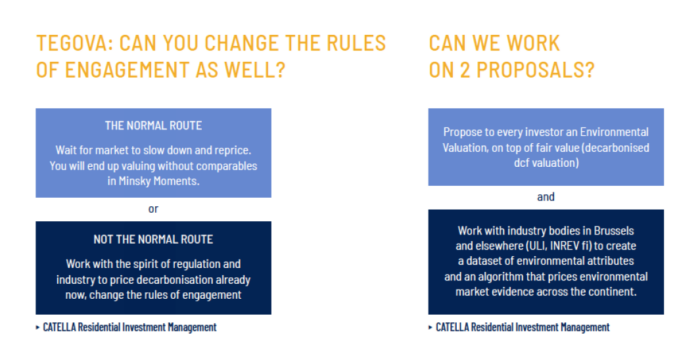

We’ve come from a world where Milton Friedman stated that the only raison d’être for an organisation is to create financial value for its shareholders, to one where pension funds and other institutional investors refer to the UN Sustainable Development Goals as part of their investment strategies, which means they are changing the ‘Rules of Engagement.’ If a large part of society believes the prevailing economic system does not produce fair and positive results, then that disconnect forces the system to change. Ipso facto therefore, are the Rules of Engagement in real estate valuations, as currently defined, still fit for purpose? A profession that works with backward-looking ‘comparables’ is just not configured to handle the forward-looking and currently ‘un-benchmarked’ notion of decarbonisation in real estate, so we need a new approach in the valuation framework to bring this onto the profit and loss balance sheet.

Double Materiality at the Asset Level; Moving the Needle from value to ‘Value’

Catella has started a €2.0 billion investment programme to roll out 100 residential towers across European markets based on French engineering design company Elithis’ revolutionary combined construction and socio-economic building concept successfully trialled and proven over the last three years in Strasbourg: The world’s first ‘energy- positive,’ residential tower at scale that produces more energy than the building and the tenants consume, including their private usage of energy. The complete, or virtual, eradication of domestic energy bills, results in total ‘effective’ rental costs being 5-10% below the average of a comparable asset in the neighbourhood in which the Elithis towers are located. This significantly boosts household incomes and means they are always affordable within the community context of where they’re built.

Creating a self-sustaining residential asset that shields the consumer from unprotected exposure to volatile energy market prices, particularly relevant in Europe’s current gas crisis, gives Catella more leeway to experiment with integrating the societal ‘S’ element deeper into our ‘dark green’ ESG investment model. Energy cost savings are effectively translated into a tool to maximise social impact.

For example, we can prioritise boosting the purchasing power of a single mother with two kids and a job, because we know that housing affordability is a big challenge for precisely this type of household, with women on average earning 10% less than men in European economies.

“ If property valuers do not move towards including forward-looking decarbonisation costs in their assessments, […] they will further disconnect from the direction in which society and lawmakers are moving […] ”

Similarly, we can tackle often implicit housing market discrimination against minority groups through proactively influ-encing the composition of our tenant mix to ensure it reflects the diversity of the broader city community in which the Elithis towers sit. Here too, energy cost savings can be directed towards benefitting those who may otherwise have fallen below the ‘40% of disposable income’ hurdle that constitutes the base threshold for ‘affordable rents’ within the EU.

We thus avoid the ‘moral hazard’ that is usually contained in ‘broad brush’ public housing policies with a one size fits all strategy that produces the unintended consequence of also benefitting those who are not in need. The social housing corporation trap where many tenants that are not really entitled to live in these homes, because their incomes are too high, are effectively being subsidised at the expense of other possible tenants whose social need is greater, but are being shut out. Catella also avoids the ‘moral inflation’ of some investment managers who claim they are addressing housing affordability simply by the fact of adding new supply.

But valuers can’t price these ‘intangibles’ or double materiality. The profession acts as though decarbonisation has zero cost and the Elithis towers are treated in the same way as carbon heavy assets from the fossil fuels and energy labelling era. Catella’s investors get no ‘greenium goodwill’ in the valuation of Elithis assets, or on our fund balance sheets, because the investment in the decarbonisation process is invisible according to valuers and this is creating a substantial impediment to innovation for the energy transition in the built environment. The price point mechanism, central to capitalism, is not yet working to be able to move us from financial returns to real stakeholder returns.

For example, I might want to buy a building for one of the Catella Residential funds for say €20 million and I calculate the decarbonisation investment costs for this asset at €2.0 million. In the final round of bids I then go to my acquisitions team and say can you please lower your offer to €18 million, because that will then include the actual decarbonisation costs. They would roll their eyes and think I’d taken leave of my senses. We all know that would kill the deal. But every- one is facing the same problem and no single company, however big, can change this system alone. It is a type of ‘common good’ problem that has to be tackled industry-wide, through organisations such as ULI, TEGOVA, INREV and others, because global warming is the biggest challenge of this century, as far as we can know, and we’ll only be able to find game-changing solutions through collaboration.

Climate change is best handled in a two-pronged way at the international and local levels, but the nation state still retains the reins of power. We are fortunate in Europe to have the European Commission, which has been empowered to propose new supranational leg-islation. The upcoming ‘Fit for 55’ legislative proposal means the EC will be bringing the real estate and construction industry closer to a climate action level comparable with the automotive industry, and rightly so. The car industry will decarbonise by 2035, moreover fossil fuel cars will be banned from many cities by their local authorities before 2030. It is logical to expect the same for real estate.

If property valuers do not move towards including forward-looking decarbonisation costs in their assessments, because this isn’t in the existing valuation standards, they will further disconnect from the direction in which society and lawmakers are moving and may find new rules thrust upon them without significantly influencing their form.

Confusing Energy Ratings with Decarbonisation Costs and Pricing the Route to Paris

Great progress has already been made in EVS 2020 which references the principle: “include forward- looking energy ransition costs into your valuation”. But if the principle is there, how do you execute?

Catella’s approach to pricing our investment in decarbonisation is imperfect, but practical and transparent. We list the component units to be assessed within the asset, whether that’s solar panels, windows, the elevators or heating system, etc. and arrive at an approximate number for the operational cost of doing this, which we’ve found averages around 5%-15% of the value of the building based on the index-based tool we’ve developed. Of course, maybe 20%-50% of these outlays could also be folded into the long-term maintenance programme for the building, there is some natural replacement, and there are also energy cost savings, but it is still a significant gap.

I’ve asked developers what they think the decarbonisation costs are of new buildings we are buying from them and they usually say ‘zero’, because of the high energy efficiency ratings they’ve been proud to achieve. But that’s absolutely the wrong answer. There’s some corre-lation between the two, but there is only partial causality.

We need to start thinking about technology and including it in our financial projections, because some decarbonisation technologies applied in buildings are expensive upfront and like most innovations get cheaper over time. We have to be able to plot the timeline on which we can decarbonise the built environment to arrive at the Paris climate targets in eight, 15, or 30 years, depending on the capabilities of the companies in our industry. To do that we must be able to utilise the discount factor from a place in time by ending up with a net present value for decarbonisation costs.

Real Estate’s ‘Minsky Moment’ of Moral Materiality

A Minsky Moment’ refers to the onset of a market collapse after an unsustainable bull market characterised by a ‘tipping point’ where the market’s perception of value rapidly changes. The abolition of slavery could be seen as a moral tipping point, where society’s mainstream view changed and it became abhorrent to use human beings as goods to be traded. Ethical ‘Values’ replaced financial ‘valuations’ of people and eventually slaves become workers with rights and wages and these costs were moved onto the balance sheet.

I believe we may be approaching a Minsky Moment of double materiality in real estate valuations, where it becomes morally unacceptable to invest in buildings whose owners are either not decarbonising their standing assets, or constructing new ones that are not operationally carbon neutral, or carbon negative. Because by doing so we would be ignoring our individual ethical responsibility to do the uttermost we can to limit the extremes of global warming and the catastrophe it will unleash on this generation and those of the future.

We can already see the possible precursors of a Minsky Moment repricing, like the foreshocks before earthquakes, where certain assets are taking longer and longer to sell, and some are being taken out of the market.

Where do We Go from Here?

Every single one of us in the industry should take a little personal responsibility. If we do, then together we’ll have the power to really make an impact. Let’s start with valuations. How difficult would it be to propose to each client an ‘Environmental Valuation’ alongside the Market Value valuation — adding say 10% to the fee? Secondly, material data are currently scattered in different unconnected formats in a plethora of organisations. Vital data for our ‘common good’ contained in organisational or personal ‘silos’ should be pooled and become collective intelligence. We are blocking the road to achieving the Paris Climate Accords goals when these data are not generally accessible and sometimes hidden away, rather than being enhanced to produce knowledge, insight and value.

Would it not be an idea to develop a centralised datapool of valuations, enhanced by already existing image and language algorithms and the profound knowledge of our industry’s stakeholders? This is a common good problem, we should mutually disarm from funding our particular interests by lobbying one-by-one in Brussels. A ‘peace dividend’ in lobby funding could then be channelled to despatch our best people to Brussels to work out and embrace new innovations, crack the most difficult challenges, then turn to the Commission with a single voice and accelerate the real estate industry’s journey to a net carbon neutral built environment. Sharing data will speed up the solution to the decarbonisation pricing challenge we have in front of us and in a much more precise and cost effective way than the industry’s current approach.

Real estate industry stakeholders, associations that cover the entire value chain from tenants, valuers and developers, to end-investors, need to engage with each other to find solutions to the dilemmas of decarbonisation and then work with regulators to turn these into rules that can be implemented in the most efficient way. If we don’t, then regulators could push through legislation which lacks the insights and illumination provided by the vast experience and profound knowledge of our industry’s stakeholders. This is a common good problem, we should mutually disarm from funding our particular interests by lobbying one-by-one in Brussels. A ‘peace dividend’ in lobby funding could then be channelled to despatch our best people to Brussels to work out and embrace new innovations, crack the most difficult challenges, then turn to the Commission with a single voice and accelerate the real estate industry’s journey to a net carbon neutral built environment.

“ How difficult would it be to propose to each client an ‘Environmental Valuation’ alongside the Market Value valuation — adding say 10% to the fee? ”

“ Would it not be an idea to develop a centralised datapool of valuations, enhanced by already existing image and language algorithms? ”

Source: European Valuer, the publication of The European Group of Valuer’s Associations (TEGOVA).